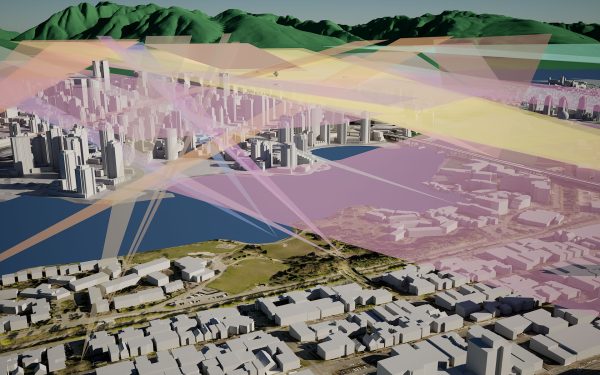

Model of Vancouver View Cones. Courtesy of Stephen Bohus.

What is the true value of a view? This question should be top of mind among all Vancouverites as the City of Vancouver Council considers removing the current view protections that have remained in place for 30 years. With the Council review set for tomorrow (July 10th), it seems appropriate to remind us—the Vancouver community—of their relevance as a gift to the public: one in danger of being handed over to wealthy patrons who can afford to live above the city of general public within their artificial mountains.

Views of the North Shore Mountains and our natural environment are easily taken for granted. We appreciate them daily from different parts of the city—sitting reflectively on the beach of Trout Lake Park, or looking over the city from Queen Elizabeth Park and simply walking along parts of Main Street, to name just a few. It’s so common that we forget—or perhaps do not know—that within Vancouver, they are “designed”. These are not random and they certainly do not exist at all.

Over three decades ago, the need to protect significant sightlines in the name of the public good was necessary. It was determined that certain sightlines, particularly of the North Shore Mountains, were to be preserved for public enjoyment amidst urban development. The concept was first introduced in the 1980s and made official in 1989, with Council-approved protection of these public views. The policy was created on the enlightened idea that certain aspects of our natural environment were too important to give over to private interests.

As stated City of Vancouver website, they were created to balance economic growth with housing while “preserving landmark views for future generations.” I italicize the latter to emphasize that they were created in the service of the public good—that is, something provided to ALL members of our city, visitors included, without profit. This is to say that everyone can and should benefit from it without reducing its availability to others for decades to come. Implied in this was the humble admission that they would be lost if given over to the market. Government intervention was necessary to ensure they remained accessible to all, promoting social equity.

But their significance goes beyond this, as we all know: these views are integral to Vancouver’s cultural identity and sense of place, contributing greatly to the aesthetic quality of the urban environment. We all know this inherently….just imagine Vancouver without views to the mountains. Without the Two Sisters? Without views of the Triple Crown Mountains?

These protected sightlines have become a defining feature of Vancouver’s cityscape. Millions of people enjoy them annually both passively—while meandering about the streets or some of our parks—and actively, seeking out to specific parts of the city to enjoy them. No fee necessary. It is a gift given by forward-thinking leaders who used them to limit building heights and placements to ensure that views of the mountains, water, and other natural landmarks remain visible from various vantage points across the city.

An enlightened leadership of today would recognize that the policy did not go far enough. Many argue wisely that their creation was ethnocentric and could have done more to accommodate the insights and values of the First People who inhabited the land for centuries before George set foot in the area. This is still possible, of course. Imagine expanding the list and policies of ‘significant’ views to include other cultures. This is certainly a pipe dream given the City’s motion to move in the opposite direction.

The view protection policy—and the public good of present and future generations that it is founded on—is in danger, courtesy of a Council that seems to be dead set on privatizing all aspects of urban life and widening the current socio-economic divide. Eliminating view cones monetizes and privatizes views for the wealthy. Only those who can afford premium real estate will have be privileged access.

Is this progress?

If so, I’d like to know by what measure. Based on Vancouver’s current direction doing so will open the city up to unrestricted development—creating a city dominated by tall buildings. One that will cover the natural landscape that characterizes the city and ultimately diminish its unique urban identity.

Preserving public access to our natural beauty, upholding Vancouver’s cultural and aesthetic values, and promoting social equity, should be non-negotiable. That the Vancouver City Council is considering their removal demonstrates how far the City has moved from a community-oriented city…and is a large slap in the face to all Vancouverites, and the enlightened minds that thought to put future generations before their own.

***

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning.